Some commentators have described Mario Draghi’s plan for rebooting the Eu ropean Union as a ‘breakthrough’. It is often presented as offering a radical change of course in EU economic policy, even if it is admitted that the plan is unlikely to be implemented, given the difficulties finding agreement on an increased common European budget. Here, we will argue that even this more limited claim is not true.

The discourse of the Draghi plan is articulated on two levels, with an explicit narrative that attempts to conceal its real implications. The global balance, Draghi says, is changing, as a world divided into three blocs is emerging: China, the US, and then the bloc that Europe still needs to forge. Doing so will not be easy, and in some sectors the accumulated lag is so bad that it can no longer be caught up.

According to the Draghi Report, Europe lacks the scale to compete, because despite having liberalised the circulation of goods and capital, market imperfections still exist, severely constraining its progress. Too many national regulations segment the market. There is too strong a power of veto at the European level, which prevents rapid and thus effective decision-making. There is too weak a financial system, which cannot channel resources and allocate them optimally. On top of these market imperfections comes another massive problem: China, which plays rough, given the state direction of the economy.

To all this there is, for Draghi, only one remedy: making the European market a truly single market, removing institutional constraints and creating continental-scale enterprises that can compete on the global stage. In this way, it will be possible to ‘level the playing field’. The focus will have to be placed on those strategic sectors where Europe has lagged behind the least and thus can still catch up. These could include some kind of ‘green’ manufacturing and clean technology sectors. This is an arbitrary and short-sighted choice, since other kinds of production — even ones linked to the double green and digital transition — are given up as lost, however necessary they may be.

Another strategic focus in the Draghi Report is the defence sector, whose main weakness has dramatically emerged during the conflict in Ukraine: the total lack of interoperability between military kit and devices from different countries, making their use, maintenance and ammunition supply totally in efficient, if not impossible. For Draghi, a European industry based on a single standard must necessarily be built in this area.

To do all this, a massive investment plan is needed, even bigger relative to EU GDP than the Marshall Plan: €800 billion per year, to be raised by ‘mobilising private savings’. Yet this means the same private savings that Europe is unable to get out of its pockets because of our financial systems, which are too fragmented and underdeveloped compared to those of the United States.

What counter-narrative lurks behind this public discourse?

Draghi recognises that the United States is seeing its hegemony increasingly jeopardised, with China having now clustered the so-called Global South around itself and openly contesting US power. Europe finds itself squeezed between the two blocs, with no more access to raw materials and energy, with no more outlet market for the industrial production of its manufacturing locomotive (Germany) and with an accumulated backwardness that will be impossible to make up in some strategic sectors, indeed so much so that in some sectors it is not even worth trying.

With the eastern bloc becoming hostile, Europe must become an appendix to the star-spangled bloc: an outlet market for the products of its industrial apparatus and its raw materials, a source of rent extraction for its financial system.

Europe can, however, specialise in those sectors where the accumulated backlog is not substantial, and the capacity endowment fairly satisfactory. This is, for Draghi, where all efforts should be targeted — the so-called ‘green’ sector. Then there is defence, with the already mentioned need to adopt a uniform standard.

To do this, we need planning. This planning, however, more closely follows the American than the Chinese model, i.e. would be driven by private multinationals and not by the state. In fact, Draghi explicitly supports the need to have large multinational oligopolistic players that can operate without having to submit to all the rules, especially national ones, that still exist in Europe. We must get rid of the norms that reduce the opportunities for oligopolies to maximise profit; and we must reduce the power of veto in the hands of individual EU member-states.

How can we obtain the €800 billion per year needed to fuel this process — and import from the United States what Europe cannot produce — without changing the Stability and Growth Pact? Draghi's answer is clear: ‘by mobilising private savings’.

In other words, individual European countries will have to divert part of their current expenditure to this European investment plan — to provide the private sector with adequate financing. Inevitably, this will reduce the coverage of public services — transport, social housing, schools, universities, healthcare — thus forcing citizens to resort to the financial system — university loans, supplementary pensions, health insurance, mortgages, etc. In this way, for every eurodiverted to the European plan another euro will be injected into the financial system by citizens themselves (probably even more than one euro, since the service provided by the private sector will be more expensive than the public one). For the right-wing Keynesian Draghi, the multiplier is an all-financial one, based on the privatisation of public services and on private debt.

What could tip the scales in order to convince the German leadership of all this? Apparently, the reassurance that much of the productive investment will be concentrated in its economic area of reference. If the need is to catch up, it is obvious that the constraint will be to invest everything where there is already a starting capacity; and especially in the ‘green sectors’, the production capacity currently lies in Germany. The other countries, Draghi says, need not worry: the productivity gains that can be achieved will benefit everyone, regardless of the geographical location of the investments. So, as usual, industrial investments will have to be in the core of the EU, while other countries will make do with ‘indirect spillovers’.

Is this an abrupt change of course, as compared to the original goals of European integration?

When it comes to the creation of favourable conditions for large multinational oligopolies, certainly not. On the contrary, it can be argued that this has been the strategic objective of European integration from the very start. The official narrative, centred on the free-market concept, argued for the need to liberalise markets and create the right conditions for competition in order to reduce prices for the consumer through the market’s ability to achieve optimal allocation. And indeed, prices did fall at first, but as a consequence of an entirely different mechanism.

In reality, a process of capital concentration has been fostered, starting the process of consolidation of oligopolies. During this phase, the prospective oligopolist takes advantage of its economies of scale to push prices down. This achieves two things: it provides credibility and political momentum to the public discourse; it either pushes smaller undertakings out of the market or subjects them to the command of the large OEMs (original equipment manufacturers), of which they are direct or indirect suppliers. In other words, OEMs exercise their market power not only in the outlet market for their products — where they operate as oligopolists — but also in the purchase market for their inputs — where they act as monopsonists (single buyers), i.e. they dictate rules, prices and working conditions to their supply chain.

The emphasis on attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) also pointed in the direction of increasing the concentration of capital. At the end of the consolidation process, the oligopolists can finally make use of the accumulated market power. At this point, the existence of the oligopolies can be legitimised with the rhetorical paraphernalia unleashed by Draghi and briefly summarised above.

As for the goal of strategically positioning EU as the periphery of the US-led bloc, it is difficult to argue that this, too, was a strategic goal of European integration from the very beginning — whereas it is entirely plausible that this was the goal, or at least the hope, of the United States.

More likely, the European ruling class made its calculations wrong, accustomed as it was to reasoning in imperialist terms, thinking that it could forever enjoy its rightful colonial privileges vis-à-vis a southern part of the world considered incapable of developing.

European industry: case history and diagnosis

According to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (article 173), industrial policy in the EU specifically aims at: (1) ‘speeding up the ad justment of industry to structural changes’; (2) ‘encouraging an environment favourable to initiative and to the development of undertakings throughout the Union, particularly small and medium-sized undertakings’; (3) ‘encouraging an environment favourable to cooperation between undertakings’; and (4) ‘fostering better exploitation of the industrial potential of policies of innovation, research and technological development.’

In other words, industrial policy must secure framework conditions favouring industrial competitiveness. As such, the main industrial policy tools defined and implemented in the EU are tax reduction for enterprises; anti-trust and competition policy; incentives for FDI; education and training policies; in frastructure, funding and management for incubators and cluster formation; R&D subsidies and/or tax credits; establishment of research centres and the dissemination of research findings; skill formation schemes, etc.

The approach is very clear: avoiding any public intervention in the economy — public ownership most of all, but also public planning, public definition of priorities, public choice of sectors etc.

This meant reducing the public sector’s role to merely delegating any strategic decision to the free market — i.e., to private capitalist firms. In this way, the public sector’s sole task is a matter of creating and financing the best possible environment for private capitalist initiative — eliminating ‘market failures’. These European policies have favoured the concentration process on the one hand, and multinational-led restructuring on the other.

Though asserting the need to favour small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and prevent excessive market concentration,

[t]he Commission has cleared the vast majority of mergers uncon ditionally as it found that no competition concerns arose. Since the early 2000s, it has concluded that the merger may significantly impede effective competition in about 5 to 8% of all notified mergers annually. … The Commission has prohibited 30 mergers since 1990, of which 12 since the adoption of the recast Merger Regulation in 2004, which is less than 0.5% of notified mergers.1

According to the European Commission

[t]he share of high concentration industries increased substantially in the last two decades. The proportion of industries where the largest four firms account for at least 50% of the industry total doubled, from about 16% to near 37%. Even when weighted by industry size, the evidence shows a similar 60% increase, from 12% to 18%.2

These data highlight the strength of the process of capitalist concentration. Furthermore, during these years, we have witnessed a far-reaching reorganisation of the European industrial structure, in particular through relocation to low-labour-cost countries, also located within the EU.

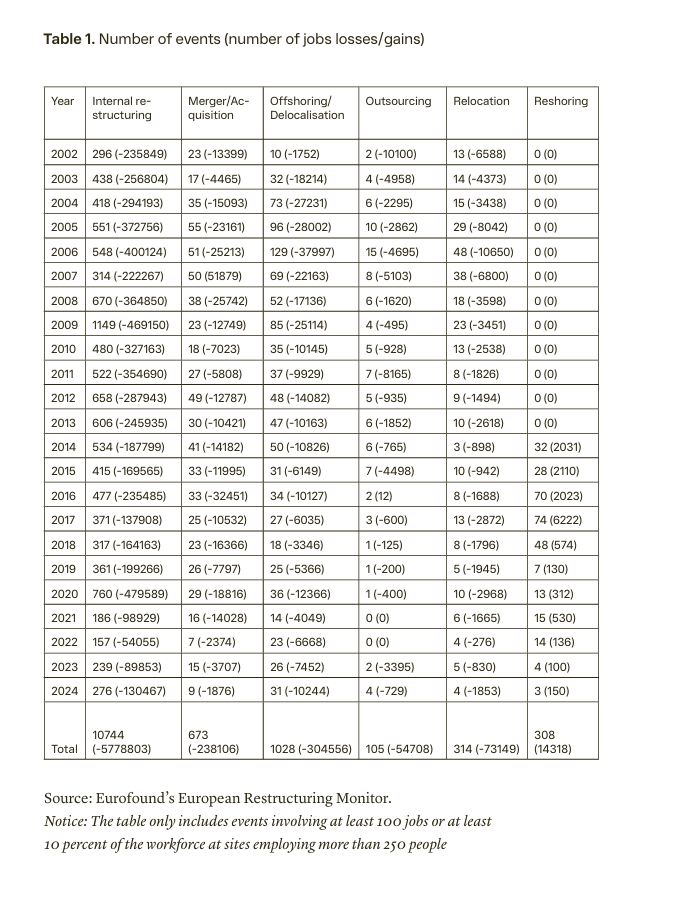

Table 1 reports the number of notified large-scale restructuring events by restructuring type. Overall, during the period considered, almost 6.5 million jobs were lost or displaced. In particular, internal restructurings caused the loss of 5.7 million jobs; almost 250,000 jobs were lost due to delocalisations, relocations and outsourcing.

What, then, was the role of the European institutions in shaping industrial policies?

As stated by the European Parliament,

[t]he failures of industrial policies have been emphasised from different perspectives in recent years. The discussion of such failures echoes in the debate today, in particular with reference to excessive government involvement in the private sector leading to favouritism and rent-seeking. The failures arise from the fact that in the past industrial policy was picking the winners, by selecting and promoting national champions. Such an ‘‘old’ ‘ industrial policy consisted of vertical or sectoral top-down interventions. This type of intervention is subject to the criticism that governments are not particularly good at picking winners.3

In order to avoid ‘the traditional top-down designs … in which the government, as ‘principal’, provides the guidelines for the private sector, as ‘agent’’4 a ‘new industrial policy’ is required. This must ‘be embedded in private sector networks’.5 A possible route to achieving this goal, according to the European Parliament, is the creation of innovation systems.6 Moreover, the document stresses that ‘promoting industrial clusters is a way to avoid favouring, in a discretionary manner, particular manufacturing industries’7 which can be done, e.g., by public/private partnerships and specifically by incentives to collaboration between public (-funded) universities, carrying on research activities, and private enterprises, drawing the advantages of research outcomes.8

The mainstream narrative goes as follows: the state should facilitate the integration of local firms into value chains. Once integrated, the state should favour the ‘upskilling’ of workers and the ‘upgrading’ of companies’ technological capacities, for them to move to ‘higher value-added’ market segments. The key for upgrading is improving productivity through innovations,9 acquiring new capabilities or moving from a global value chain in one industry to an other. Attracting foreign direct investment is critical to achieve this objective.

We can thus conclude that, over the past decades, European institutions have favoured increased concentration, preventing only 0.4 percent of merger/acquisition transactions and leaving the way open for relocations. The role of the public sector is confined to creating the best conditions for private enterprise, limiting itself to encouraging upgrading. Competitiveness has been identified as a key objective. The ‘old’ industrial policies, based on favouring particular manufacturing sectors, have been discouraged and disincentivised, if not explicitly banned through regulations on state aid.

A closer look at the Draghi Plan

Draghi must necessarily begin from an admission of the failure of European industrial policies, especially when compared to those rolled out in the US and China.

In some sectors, the cost disadvantage is now so great that the only plausible approach is to import the necessary technologies, diversifying supplies to limit dependencies.

In other sectors (e.g. automotive), the EU must encourage FDI in Europe, while also developing measures to offset the cost advantages caused by foreign subsidies. The Draghi Report seems to call for Chinese investment in Europe, while at the same time proposing to put tarifs on products made in China.

Finally, there are industries where the EU has a strategic interest in ensuring that European companies maintain know-how and production capacity. Europe should therefore increase the long-term ‘bankability’ of investments in Europe, e.g. by imposing requirements on local content, to ensure a minimum of technological sovereignty.

In this regard, the Report argues for requiring foreign companies intending to produce in Europe to set up joint ventures with local companies.

The Report identifies one of the causes of Europe's weakness in technology as its static industrial structure, characterised by low investment and low innovation. Draghi contrasts the European case with that of the US, where the three companies spending the most on research and innovation (R&I) moved first from automotive to pharmaceuticals in the 2000s, then into software and hardware in the 2010s, and then into the digital sector. In contrast, he suggests that European industry remained static, with automotive companies still dominating in R&I spending.

Thus, while the US favoured the use and production of new, innovative technologies by redirecting resources to sectors with a high potential for productivity growth, investment in Europe remained concentrated on mature technologies and in sectors where productivity growth rates are slowing down.

As for Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Report begins by criticising the limits on data collection and processing in Europe, which create high compliance costs and hinder the creation of large, integrated data sets for training AI models. This fragmentation would put the EU at a disadvantage compared to the US — where companies rely on the private sector to build large datasets — and China, which can leverage its central institutions.

On the industrial side, the Report argues for faster, low-latency and more secure connections, lamenting how far the EU is lagging behind the Digital Decade 2030 targets for fibre-optic and 5G deployment. The investment needed to support EU networks is estimated at around €200 billion to ensure full gigabit and 5G coverage across the EU, but this investment is well below that of other major economies.

The main reason for these low investments, according to the Report, is the fragmentation of the European market, which makes the fixed costs of network investments relatively more expensive for EU operators than for continental-scale companies in the USA or China.

The Report fails, however, to recognise that this fragmentation was the result of the choices made to liberalise the sector (taken at the EU-wide level), which were pursued with great determination by the European Commission: between 1988 and 1997, no less than 11 directives were approved which were, in various ways, committed to this liberalisation process in the sector.

The Report proposes consolidations (i.e. mergers, acquisitions, etc.) between the companies in the sector that have in the meantime largely been privatised. This would move from the condition of a public/state monopoly (which ensured the development of these services, and especially the infrastructure), to a private one.

The Report goes on to argue the need to promote coordination and data sharing between industries to accelerate the integration of AI in European industry.

Obviously, the Report sees the use of AI in factories only from the corporate point of view, i.e. as a tool to increase profitability. The workers' point of view is not even mentioned in the Report, which also goes so far as to identify in which sectors AI should find the fastest implementation — automotive, advanced manufacturing and robotics, energy, telecommunications, agriculture, aerospace, defence, environmental forecasting, pharmaceuticals and healthcare. Here too, the public sector should step in with funding to support private business.

Several times in the Report, the high energy costs facing Europe are emphasised, especially in comparison to other areas of the world. This is compounded by concerns about shortfalls in generation capacity and networks, which could impede the spread of digital technologies and electrification of transport.

Again, there is a complete lack of an assessment of the reasons that led to this situation, and in particular a complete lack of an assessment of what the liberalisation process of the energy sector has entailed; however, the Report acknowledges the responsibility of European rules in determining the current situation: ‘market rules in the power sector do not fully decouple the price of renewable and nuclear energy from higher and more volatile fossil fuel prices, preventing end users from capturing the full benefits of clean energy in their bills’.

At the same time, the Report does not address the problem of high gas prices, resulting in part from the speculative behaviour of the financial players who now dominate these transactions, and in part from Europe's geopolitical choices, in particular that of cutting off supplies from Russia. Gas will be needed during the transition phase, so the problem should be addressed. The Report does not do this. It does, however, acknowledge that these geopolitical choices have had a major impact:

With the loss of access to Russian pipeline gas, 42% of EU gas im ports arrived as LNG in 2023, up from 20% in 2021. LNG prices are typically higher than pipeline gas on spot markets due to liquification and transportation costs. Moreover, with the reduction of pipeline supply from Russia, more gas is being bought on LNG spot markets both in the EU and globally leading to stronger competition’.

Draghi forgets to point out that a large part of LNG supplies come from the US, which, of course, has been doing brisk business with Europe during this period.

On the subject of decarbonisation, the Report emphasises the huge amount of investment needed by the most energy-intensive industries (EIIs: chemicals, base metals, non-metallic minerals, and paper) to decarbonise their production: an estimated €500 billion investment over the next 15 years, while for the hardest-to-abate transport sectors (maritime and aviation) the investment needed will be around €100 billion a year between 2031 and 2050.

Two instruments are proposed to address the situation: Carbon Contracts for Differences — financial instruments aimed at protecting, through a state guarantee, investments in green technologies by companies — and competitive auctions by the European Hydrogen Bank.

The European Hydrogen Bank was launched in 2022 by the European Commission to support investment and business opportunities for renewable hydrogen production in Europe and worldwide. The instrument works through a system of auctions for the allocation of financial support — the next auction will open on 3 December 2024 and allocate up to €1.2 billion to renewable hydrogen producers located in the European Economic Area (EEA).

As usual, the public sector is to give up on playing any role, limiting itself to the function of a mere provider of financial support to correct market failures and/or reduce business risk.

On the subject of clean technology production, the Report merely states that Europe has strong innovation potential that can enable it to meet domestic and global demand for clean energy solutions, a sector in which Europe is presented as a leader.

However, Draghi himself acknowledges, ‘it is not guaranteed that EU demand for clean tech will be met by EU supply given increasing Chinese capacity and scale’. Evidently, without a different regulation of international trade, European industry risks being wiped out.

However, his Report appears reticent in proposing concrete solutions: it is said that emulating the US approach of systematically shutting out Chinese technology would delay the energy transition and impose higher costs on the European economy. It would also be costly to introduce tarifs, as more than one-third of the EU's manufacturing GDP is absorbed outside the EU, compared to one-fifth of the US’s.

While a trade war is certainly not desirable, the weakness of the argument lies in the fact that it is recognised that one third of manufacturing GDP is exported outside the EU: this is a very worrying figure. The EU market has 448.8 million inhabitants, to which should be added those of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries (Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liech tenstein, totalling 14.7 million) and the United Kingdom. This means that instead of focusing on an export-oriented model, Europe could focus on domestic demand, obviously by raising wages.

The Report does not fail to mention that the EU is the world's second-largest producer of solar panels, wind power plants and electric cars. In some of these sectors, Europe had achieved a first-mover status which it then proved unable to maintain. In the case of wind-power plant production, the EU has a strong position, but faces new challenges: for example, while European wind-turbine production is able to serve 85 percent of domestic demand, it has lost significant market share to China in recent years, falling from 58 per cent in 2017 to 30 percent in 2022.

In other sectors, the EU retains its technological lead (electrolysers and coal capture/storage plants), but many European manufacturers prefer to produce on a large scale in China, due — according to the Report — to higher construction costs in the EU, delays in issuing permits, and difficult access to raw materials. Once again, the Report invokes the concept of a level playing field, suggesting that countries who do grant subsidies are playing dirty.

EU funding, according to the Report, is both weak and fragmented among different programmes, characterised by high complexity and long lead times, and generally excluding operating costs where the cost gap is more significant than in other areas of the world.

Can we do things differently?

One of the weakest and most controversial parts of the Draghi Report concerns the financing of the actions necessary for the EU's green and digital transition, and more generally for the reconstruction/transformation of the European industrial structure. This calls into question the issue of investment, which has never really been addressed by EU policy decisions except in the classical terms of ensuring that investment is profitable.

The fall in economic growth in the developed countries is based on both wage compression and on the reduction in private and public investment. On the one hand, the austerity rules of public spending have weighed heavily on the reduction of public investments. On the other hand, the dogmas that assign the decision of how much, how and where to invest to the private sector alone have affected industrial investment. In this logic, it was assumed that the financial markets are efficient, and so the allocation in terms of investment that they determine is the best possible outcome. Hence, the public authorities must not interfere with these markets.

This dogma has at least two consequences. Firstly, it makes the level of investment depend on the capitalists' expectations of profit, and more specifically on the expected rate of profit, given by the ratio of profits to the capital stock: it follows that if the change in profits does not grow as much as the change in the capital stock, the rate of investment falls.10 So, in this case a low expected rate of profit is likely to stop investment.

The second negative consequence is related to the excessive enthusiasm that high profits can generate. The financial crises have shown that banks and asset managers follow the trend, so they can create waves of over-investment in some sector driven by expected profits, but when the bubble bursts even good counterparts are not able to pay back their debt (see Hyman Minsky’s f inancial instability hypothesis). Hence, leaving the investment decision to private companies is unstable by definition.

A further point is that financial markets only care about profits: public services and investments that are important for long term economic growth and for social goals, may also not determine large profits, or even profits at all. In addition, financial markets do not only think of profits per se, but of high profits in the short term: the exact opposite of what would be needed in the case of infrastructure, equipment and facilities required for industrial transition.

The facts show that private finance only comes into play when states provide large amounts of public money, such that the investment risk is reduced to zero.

Again: even when private finance decides to support an investment, the single green projects are not useful if they are not part of an overall plan for the transition and considered as a whole; but financial markets are not interested to do. Only public planning could do this. And public planning should be accompanied by (also public) instruments for financing investments.

Hence, what is needed is a direct intervention through a public operator, like the National Development Banks (NDBs): these are ‘Government owned f inancial institutions with the objective of fostering economic or social devel opment by financing activities with high social returns’.11 They can invest in socially valuable, but unprofitable projects; and in highly illiquid very long term projects. Examples of NDBs include the Italian Cassa Depositie Prestiti, the French Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau etc.

An NDB has two main sets of goals: the first one in terms of development (overall development, the development of specific sectors, areas, etc.), the second one in terms of financial stability and the functioning of the financial system.

The social and environmental goals solemnly declared by the European Commission — even when they are truthful — are completely hollow statements in the light of the deficit and debt rules established by the Maastricht Treaty onwards, which prevent these aims from being seriously pursued.

The NDBs are classified outside the perimeter of general government, resulting in the deconsolidation of its debt from public debt according to Europe’s ESA 1995 system of accounts ;12 therefore, while having to respect the constraint to comply with the rules and behaviour typical of a market unit, they can activate investments without running into the restrictions of fiscal and public budget policies imposed by the EU. Hence, in the specific EU situation, NDBs related industrial policies can rebalance the Maastricht Treaty’s austerian framework. If politically oriented, they can become the financial arm of EU social and industrial policies.

The second goal (financial stability) is clear: financial markets are highly pro-cyclical because banks and financial operators lend too much in the up swing stage of the bubble and they escape when the bubble starts to crumble, producing credit crunch and a more painful recession.13 On the contrary NDBs can stabilize the situation, by reducing banks’ myopia and markets short-termism (as observed already by Minsky)14 and allowing for a more inclusive and democratic finance, because they can mobilise capitals for long-term investments designed to achieve social and environmental goals.

The investments mentioned in the Draghi Report need long term planned strategies and more stability (less short-termism) in the financial system. So, due to their long-term orientation, NDBs are financial operators that can implement investments in the industrial structure, which must be partly rebuilt, partly expanded and partly reconverted to achieve environmental goals and, this is a key issue for the political and trade union left, to achieve full employment.

On the contrary, private finance in the green transition only happens if and when governments create a fiscal environment conducive to high profits.

Conclusions

Mainstream rhetoric on ‘upgrading’ and ‘specialisation in high value-added stages’ has supported the processes of relocation of manufacturing — considered ‘low value-added’ — in favour of design and post-production stages. In essence, labour-intensive phases have been relocated to low-cost countries, counting on the notion that they can be eternally subordinated to Europe. Making the green transition and reducing foreign dependency requires instead a re-internalisation of all manufacturing phases, starting with basic industries — especially metallurgy and chemistry — which form the material basis of any production chain.

This is where the EU should concentrate its efforts, in a process of forced industrialisation that can only start with heavy industry.

For such a process to take place, careful planning is required. However, if the big multinationals take the strategic decisions, the main objective will continue to be profit maximisation, which is in stark contrast to environmental, industrial and social objectives.

Only public planning can take over such an undertaking, without pitting the financing of the transition against the funding of essential public services.

In conclusion, while the Draghi Report's analysis of the status quo can be partly shared, the proposed solutions go in the opposite direction to the one it calls for.

Creating large public enterprises in strategic sectors, which have the entire production chain (starting with basic industry) under their control, is essential. As far as raw materials are concerned, the public R&D system should concentrate its firepower on finding substitutes for Critical Raw Materials (CRMs), thus reducing foreign dependence and competition on international markets.

Endnotes

1 European Commission, 2021a. Commission Staff Working Doc- ument Evaluation of procedural and jurisdictional aspects of EU merger control –— SEC (2021) 156 final, SWD (2021) 67 final..

2 Gábor Koltay and Szabolcs Lorincz, ‘Industry concentration and competition. Competition Policy Brief’, European Commission, 2021.

3 European Parliament, 2015. EU Industrial Policy: Assessment of Recent Developments and Recommendations for Future Policies. Directorate-General for internal policies, Policy Department, 2015,

p. 20.

4 Ibid., p. 21.

5 Nicholas Crafts and Alan Hughes, ‘Industrial Policy for the Medi- um- to Long-term’, Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge Working Paper No. 455, 2013.

6 Bengt-Åke Lundvall and Susana Borrás, ‘Science, technology and innovation policy’, in The Oxford Handbook of Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005; Franco Malerba, Sectoral Systems of Innovation: Concepts, Issues and Analyses of Six Major Sectors in Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

7 European Parliament. EU Industrial Policy, cit., p. 20.

8 Patrick Kline and Enrico Moretti, ‘Local Economic Development, Agglomeration Economies and the Big Push: 100 Years of Evi- dence from the Tennessee Valley Authority’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129 (1), 2014: pp. 275-331; Mariana Mazzucato, The Entrepreneurial State, London: Anthem Press, 2013.

9 Technological change carries as a benefit ‘the introduction of new products, greater competitiveness-based export performances, and higher profits’ (Dario Guarascio and Mario Pianta, ‘2016. The Gains from Technology: New Products, Exports and Profits’. Eco- nomics of Innovation and New Technology 26 (8), 2016: pp. 779-804, here p. 779). See also Andrea Coveri and Mario Pianta, Drivers of Inequality: Wages Vs. Profits in European Industries, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 60 (March), 2022: pp. 230-42.

10 Michał Kalecki, ‘The Determinants of Investments’, in Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

11 United Nations, Rethinking the Role of National Development Banks, New York: United Nations, 2005.

12 Franco Bassanini, ‘La ‘mutazione’ della Cassa Depositi e Prestiti: bilancio di un quinquiennio (2009-2015)’, in Astrid Rassegna no. 14, 2015.

13 Luca Lombardi and Matteo Gaddi, ‘The Case for a National De- velopment Bank: The Main Issues’, transform network blog, 13 August 2023, available at https://transform-network.net/blog/ working-group/the-case-for-a-national-development-bank-the- main-issues/.

Hyman Minsky, ‘Uncertainty and the Institutional Structure of Capitalist Economies’, Levy Economic Institute Working Paper No. 155, Levy Economic Institute, 1996